In 2007 and 2008, two research projects in the seven areas were carried out on weaving in the Dogon Country. These projects were the subject of a Master’s degree in ethnology at the University of Cologne under the direction of Klaus Schneider (Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, Museum of Ethnology, Cologne) and Michael Bollig (University of Cologne).

Objectives

Fieldwork has the goal of examining whether the ethnological study of weaving in the Dogon Country was a valid source that could aid in better understanding the Dogon history. The precise objective was to study the techniques, linguistics, history and myths referring to weaving in the different Dogon regions. The analyses were motivated by this question: can we identify, as with pottery and iron metallurgy, different weaving traditions?

Research localities

Studies were carried out in different regions of the Dogon Country, varying both geographically and linguistically :

-Logo, village on the Seno plain (Tomo kan language)

-Tourou, village on the Seno plain (Tengu kan language)

-Yawa (fig. 1), village on the Bandiagara escarpment (Tengu kan language)

-Koundougou, village on the Bandiagara plateau (Dogo dum language)

-Tangadouba and Pigna, villages on the Bandiagara plateau (Pignari region, Mombo language)

At the same time as studies carried out with the Dogon, surveys were done with weavers attached to the Peul and a Bamana weaver in the town of Segou.

Methods

The methods used were participating observation, semi-direct interview, informal conversation as well as photography as a means of communication to clarify information about local traditions and past techniques.

Weaving in the context of textile production in the Dogon Country

The different stages in the process of fabrication are well-defined and distributed between men and women. With the revenue that women earn from the cultivation of their own fields, they buy cotton and other raw materials and spin the thread manually. The thread is then given to weavers, who are always men. The men weave the overall width based on orders given by the women, and are remunerated by the latter. The women then decide if the fabric will be sewn, dyed or directly sold to merchants.

Results

The present state of research has identified three weaving traditions, particularly following the different fabrics made traditionally and currently :

The first tradition exists on the escarpment, in the village of Yawa, as well as on the plateau in the village of Koundougou. It is characterized by the production of greige width in cotton without motifs (fig. 2).

The second tradition identified is present on the Seno plain in the village of Logo. It is distinguished by the weaving of widths decorated by stripes on the warp (fig. 3). These stripes are made with beige or indigo-dyed threads of cotton, silk or fibers extracted from bombax fruits. Such widths are only used for the production of feminine loincloths (fig. 4). Each motif has a specific meaning or message.

Fig. 5 Width weaved at Pigna, for the production pour la production of oldebe blankets. Photo H. Mezger

The third tradition has been found in the Pignari region in the villages of Tangadouba and Pigna. It is characterized by the production of widths with motifs made by supplementary blue wefts, dyed with indigo, on a beige background (fig. 5). These widths are used to make oldebe blankets, which are used in many Dogon villages in traditional funerary ceremonies. These blankets belong to an ancient tradition. In the caves on the Bandiagara escarpment, several blankets with lozenge-shaped or hourglass motifs, separated by vertical strokes, were discovered. The oldest are dated to the 11th and 12th centuries AD (Bolland 1991: p. 86, 100, 184, 226, 229 and 242-243).

The weaving loom used in all of the places researched in the Dogon Country is a type typical in West Africa (Schaedler 1987: p. 92). It consists of a mobile warp with two heddles operated by pedals. We cannot yet determine if the two variants of this type of loom used are in correlation with the types of widths woven. They could also be the result of a local adaptation to different environments: models with a pit for the weaver’s feet are used on the plain, where it is easy to dig a hole in the sandy soil (fig. 6). Looms without a pit are found on the cliff and the plateau, where the rocky soil does not allow the digging of a pit (fig. 7).

Conclusions

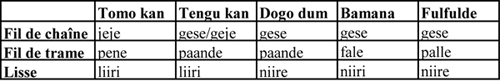

At present, three weaving traditions have been identified. Analyses of vernacular terms and oral traditions suggest hypotheses on the origins of weaving among the Dogon. The terms for warp thread, weft thread and heddle are very similar in the Dogon (Tomo kan, Tengu kan and Dogo dum), Bamana et Fulfulde languages (fig. 8). They confirm the linguistic data presented by Boser-Sarivaxévanis and his argument that the Dogon adopted weaving from the Peul or the Manding at a late date (Bolland 1991: p. 46-47). According to the oral tradition in the village of Logo, the Dogon voluntarily learned weaving from the Maabo (weavers attached to the Peul and formerly their slaves). This discourse is reinforced by customs that are still practiced today.

The many textile remains found in the caves of the Bandiagara escarpment dating from the 11th to the 18th century form a significant source of information concerning the history of textiles and weaving in the Dogon Country (Bolland 1991).

The ethnographic study carried out in a comparative and historical perspective of the profession of weaving thus constitutes a useful source for understanding the history of the Dogon.

Fig. 8 Terms for weaving in the Dogon languages (Tomo kan, Tengu kan, Dogo dum), bamana and fulfulde.

Heidrun Mezger